Asbestos, Art and Analogy in “The Long Way Home”

Science and fine art merge in Louise Penny’s asbestos murder, a metaphor for the poisonous effects of envy and refusal to change.

Hi friends,

Today, we’re sharing an essay from Caroline Delbert about art and science in “The Long Way Home,” the tenth book in the Inspector Gamache series. In it, Caroline argues Louise Penny is a “master of analogy.” Do you agree? What do you think of the use of analogy in the book?

- Aya and Elizabeth

What grabbed me about Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache books right away is their thoughtfulness. Gamache is a cop, yes; the books are undeniably copaganda, like most detective series. But within that framework, or perhaps as fruit of the poisoned tree, Gamache is kind, intelligent, dogged, and almost unbelievably moral. He’s so upright that taking down his own department in a hail of bullets only clears a path for him to come back in an even more powerful job eventually.

They do also go into a great deal of detail about the lives of Gamache, his family, and the people in the village of Three Pines where he later lives. I’d argue that Penny positions Gamache’s investigations in a much more organic way, as part of his daily life and of a career he openly grapples with during the books. She also has a gift, a knack, for casting the right mystery alongside the right theme that affects Gamache or his loved ones. She’s a master of the analogy. For proof, look at #10, The Long Way Home. The asbestos one.

Asbestos as Art

In The Long Way Home, we rejoin the action in Three Pines on a fateful day. The town’s artist, Clara, has been expecting her wayward and calculating husband Peter back after a year’s emotional rumspringa. She has prepared a typically sumptuous Three Pines dinner, but he never appears. After a couple of weeks, she tells Gamache she believes he’s missing. Together, they investigate where he’s been and where he might be going next. Gamache lets Clara lead him, which dovetails into both of their overarching stories: Gamache’s acceptance of the emotional baggage he carries and Clara’s self actualization.

Penny uses asbestos as a metaphor for the dark side of being a creative worker. In the book’s second half, Gamache rotates through several theories as he tries to figure out which of the story’s artists is the most, even murderously, envious of the others. Is it Peter? Gamache traces Peter’s journey to a cosmic garden in Scotland and to the wilds of northern Quebec. Is it the wild borderline cult leader, Norman — No Man? Gamache takes the group deep into the woods to see the ruins of an art colony.

In the end, we find out it’s the elderly art professor Massey who has schemed to kill Norman. Like Peter, Massey values surfaces: unchallenging, technically proficient art as well as the aesthetics of his school. Massey seems to have both the most and the least to lose, and the twist surprised me, at least. It wasn’t enough for Massey to drum Norman out of his conformist art school department for being a square peg in a painterly round hole. He has spent decades sending blank canvases laced with asbestos to his former colleague, who receives them as kindness. Not only has Massey been killing Norman over decades; he has been receiving and destroying Norman’s finished work, too. He has closed the system from the invasive threat of change, and the world will never see Norman’s transgressive paintings.

Asbestos as Analogy

Since I began reading the books, a lot has changed in my life. I had a more traditional career in commercial nonfiction publishing, which I loved for a long time. But in 2019, my life changed when I was let go and became a freelance writer. I took on a beat that would have surprised my younger self — hard science, like quantum mechanics and nuclear fusion -- and embarked on a journey that continues today, where I read scientific papers and news and shore up my knowledge with research and reporting.

Asbestos is symbolic, not just in Penny’s book but in our larger world. The study of science can be as whimsical as changing tastes in the fine arts, sometimes with much more serious consequences. Asbestos was hailed for its precious ability to prevent fires from spreading, and soon it was in virtually every new building. Later, when scientists realized it was also causing devastating cancers, experts calculated that it was often both easier and less dangerous to leave the asbestos tiles and other materials in place -- changing them is what let the asbestos fibers go airborne.

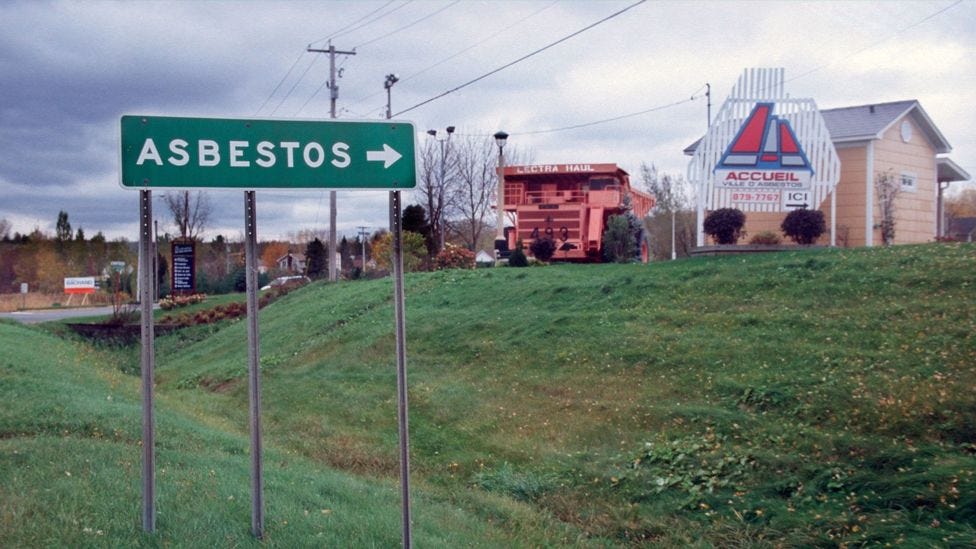

In a bit of irony, the town of Asbestos, Canada took years to change its name. Only finally doing so in 2020. A Canadian politician who lives in Cobalt, Ontario, wrote a book earlier this year that I got to mention in a piece about how billionaires want to mine Greenland’s rich supply of cobalt and other rare earth metals. How many towns like Asbestos and Cobalt are named for what is found there? There’s no convenient list. (It’s easy to find the reverse, though. Ytterby, Sweden, has four elements named after it.)

The Long Way Home is, in this way, an extended discussion of how painful change can be. “Peter was dismantling his life. Picking it apart,” Penny writes. “And replacing it with something new. [...] This new Peter was willing to try. Willing to fail.” In his search for meaningful change, Peter explores the wonders of science around him. “It’s a mix of physics and nature,” Reine-Marie says of the Garden of Cosmic Speculation. “A sort of crossroads.” He then seeks Charlevoix, a region of Quebec that was rocked -- and, by Penny’s description, beautified -- by a world-changing meteorite over 400 million years ago. Wonders like these are what led me to try my hand at science writing in the first place, like the even older Burgess Shale found elsewhere in Canada.

If the Earth itself can change in this profound way, then yes, Peter can too. Peter has spent the book as Schrodinger’s cat, both alive and dead. When we do eventually find him, he has been expressing his emotions in a new kind of painting and caring for the dying Norman. He is distinct from the cool, distant Peter from previous books, who was jealous of his wife’s success and disinterested in showing affection. Instead, it’s elderly Massey — on the surface a far kinder individual than Peter — who has spent decades poisoning the eccentric colleague he had already fired and sent into exile. He was even about Peter’s age in the book when he started acting out the destructive urge. Peter’s actions have set him on a new timeline.

Early on, the book includes a stanza from Ruth’s poetry. It feels organic when she mentions it, almost as a joke, after Gamache’s dog has created a foul smell. But it is the book’s thesis statement, really:

“You forced me to give you poisonous gifts.

I can put this no other way.

Everything I gave was to get rid of you

As one gives to a beggar: There. Go away.”

Gamache, too, goes through a transformation in the book, taking steps to move beyond the grief that has haunted him since his parents were killed by a drunk driver decades earlier. As the book opens, the detective is unable to read past the page his father had marked in the book he was reading when he died. At the end, Gamache moves towards turning the page — literally and figuratively.

Reflecting on his grief and anger, Gamache says, “A lot of things are natural, but not good.” Like asbestos. This was like asbestos. It burrowed into me.”

As a science writer, I spend significant amounts of time trying to create analogies that demystify complex topics. But it’s strangely rare to find works of art that reciprocate this work by bringing science in to symbolize questions of life, of creation, of meaning making. In this way, Louise Penny has reached her arms wide in a way that includes me, and I’m so thankful for that.

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and contributing editor at Pop Mech. She's also an enthusiast of just about everything.

What did you think of “The Long Way Home”? How do you think Penny uses metaphor in her books?

Notes from Three Pines is a short-run newsletter run through Substack celebrating and exploring Louise Penny’s Inspector Gamache books. Love Gamache or Ruth’s duck Rosa? Reply to this email, leave a comment or email notesfromthreepines@substack.com.

If you’re reading this on Substack or were forwarded this email, and you’d like to subscribe, click the button below.

Disclosure: We are affiliates of Bookshop.org and will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Lovely essay, thank you! I am a fan of metaphors, similes, and analogies of all kinds, and love seeing how LP masterfully uses them.

Insightful. I enjoyed your essay very much and hope there'll be others on Louise Penny's books.