Hi friends!

We want to extend a warm welcome to new subscribers who found Notes From Three Pines from our appearance on The Library of Lost Time. You can check out our previous essays here.

Amazon released the full-length trailer for Three Pines and a release date: 12/2/2022. Head over to watch if you haven’t already!

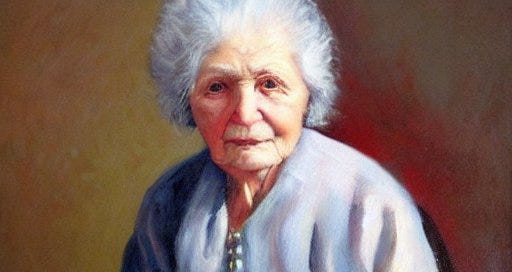

This week we’re sharing a piece on one of our favorite characters: Ruth Zardo. When we first imagined this collection a piece on Ruth was a must-have and we’re so happy Courtney wanted to write it. Courtney writes Survival by Book, a newsletter about work, love, creativity, & other life-stuff, usually with a bookish lens. We hope you love her journey into the mean world of poetry as much as we did! Do you have a favorite Ruth story? Leave a comment below!

—Aya & Elizabeth

Here are some of the words used to describe Ruth Zardo, the resident poet of Louise Penny’s Armand Gamache murder mysteries: weird, grouchy, crotchety, excessive, foul-mouthed, misanthrope, outrageous.

Despite the acknowledged power and quality of her poetry, Zardo plays an almost entirely antagonistic role in the fictional Three Pines community, providing a counterpoint of darkly comic humor against the general goodness of the residents of this quintessential (I assume!) Canadian small town. (Aside from the pesky problem of recurring murders, of course.)

She’s rude. She drinks. She drinks out of other people’s cups. She tells people they stink. She does weird things like adopt a duckling named Rosa. One of her books is titled, “I’m F.I.N.E.” which, as Three Pines residents eventually learn, stands for Fucked up, Insecure, Neurotic, Egotistical.

Yet, just about everyone who loves the Three Pine series is a fan of Ruth Zardo in some way or another. She’s not usually people’s favorite character on her own, but rather she’s everyone’s other favorite character. In fact, the word loveable is usually in front of all those other, less laudatory adjectives when people talk or write about her character.

So, what is up with that?

A long time ago, when I was teaching and living at a New England boarding school, a group of my fellow English teachers and neighbors had a party and didn’t invite me—on purpose. There was no way for me to avoid knowing that I was Not Included. I was 30 years old, but I might as well have been in 4th grade again, excluded from the cool kids’ table in the lunchroom. I remember whining to a friend about it and saying something like “the thing that hurts the most is that several of them are poets!” There was a silence on the other end of the phone line, before my friend’s deadpan response: “umm have you met poets?”

I was shocked. Was my friend implying that poets were not necessarily good and kind people? How could this be? How could anyone who has the otherworldly skill of gathering the noise of the world and transforming it into distilled jewels of meaning not have the disposition and character of an angel?

weird, grouchy, crotchety, excessive, foul-mouthed, misanthrope, outrageous . . . lovable

Anybody know anyone like this?

Couldn’t this be ok?

The thing is, people who are like Ruth Zardo make me feel safe. People who tell the truth, unvarnished, can be trusted because you know where they stand. They aren’t going to gaslight you—they aren’t interested enough in you to bother. They aren’t going to bullshit you—why would they do that when they can just say what’s really on their mind.

There’s a way in which Ruth Zardo is the perfect foil to Chief Inspector Armand Gamache. Gamache’s job is to separate truths from lies to solve problems and make the community less violent. Ruth’s job is to observe truths, lies, and violence and synthesize it into a form that feels safe. As Caroline mentioned in her essay, there’s a way that Ruth’s poems are the thesis statements of the book.

Louise Penny uses Ruth’s character to sprinkle salt and interest across the books, just like poets do for us in real life—and thank goodness. So what if they take a sledge-hammer to our petty delusions? I didn’t like it when those poets had a party without me all those years ago, but I learned some powerful home truths.

Back when I was thirty, when I was glowering over not being invited to a party, I guess you could say I was projecting. I had just finished a fine arts master’s degree in creative writing with a focus in poetry. And, although I didn’t then (and still don’t) have what I would call an angelic character, I am a better person when I’m reading and writing poetry. It’s uplifting in the way that listening to music and looking at paintings are, and the focus it takes to write it is much like meditation. And, I have poet friends who are indisputably lovely human beings — angelic even.

Still, it’s a matter of record in the historic annals of English literature that many of its best poets were drunken, philandering, mean-spirited, misanthropes. Take Elizabeth Bishop, for example.

My two favorite things about reading her collected letters are:

How you can see her workshopping language for her poems as she’s writing to people, and

How often she is writing to someone to apologize for drinking all their liquor and behaving like an asshole to their dinner guest.

With this in mind, let’s go back to the mysterious lovability of the crotchety, grouchy poet laureate of Three Pines, Ruth Zardo. She is, in addition to being a curmudgeon:

a fiercely independent person who lives alone.

a leader to whom people listen, even if they are afraid of her.

the chief of the fire department.

has fierce protective instincts that she hides by caring for a pet duckling, amongst other strange things.

writes really interesting poems. (Thank you, Margaret Atwood, for your friendship with Louise Penny and your generosity.) For example, these lines that are quoted in “A Fatal Grace” come from Atwood’s poem “A Sad Child”

‘Forget what?

Your sadness, your shadow,

whatever it was that was done to you

the day of the lawn party

when you came inside flushed with the sun,

your mouth sulky with sugar,

in your new dress with the ribbon

and the ice-cream smear,

and said to yourself in the bathroom,

I am not the favorite child.’

There is so much here in just a few lines: the happiness of sunshine, a lawn party and a child in a “new dress with the ribbon” besmirched with the words “sulky” and “smear.” There is terrible courage in making visible the secret self-doubt that we all have: “I am not the favorite child.” There is terrible honesty in calling out the ordinariness of this, too; “whatever it was that was done to you.” You could almost say it’s a mean poem, except that it’s not. It’s empathic and clear-eyed.

A couple of weeks ago, I wrote about how poetry is the cut that heals. This is the gift and burden of the poet: to take the most difficult things of human experience — things like shame, death, loneliness, and rejection — mix them in with the beautiful and quotidian life things, and spit it out in an aesthetically pleasing mix of meter, rhyme, imagery, syntax and vocabulary. It’s the art of clear-seeing honesty.

Imagine being the person that can (and indeed, must) hold this many ideas inside their mind, while sitting in a room amongst people who are talking about Buzzfeed articles about GenZ emoji use and TikTok dancing challenges.

No one should be asked to context switch like that. No wonder Ruth Zardo is grouchy.

Courtney Cook grew up in Wyoming and now lives in Vermont. She has degrees from Dartmouth College and the University of Wollongong, Australia, taught English literature for many years, and now works as marketer at TomTom. You can read excerpts from her memoir, College, a Love Story, alongside essays about books and culture at CourtneyCook.Substack.com.

Notes from Three Pines is a short-run newsletter run through Substack celebrating and exploring Louise Penny’s Inspector Gamache books. Love Gamache or Ruth’s duck Rosa? Reply to this email, leave a comment or email notesfromthreepines@substack.com.

If you’re reading this on Substack or were forwarded this email, and you’d like to subscribe, click the button below.

Disclosure: We are affiliates of Bookshop.org and will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

I can never quite picture Ruth. She is fearful and brave and hides and speaks out. I think she is a necessary character to give depth to the village. But also to give witness to the reality of the village. Everyone else seems to have found the village as a part of their quest for wholeness. But Ruth was here from childhood and her life has been hard. I always want more of her story even though we know so much already.

(Thank you for the note about Atwood. I had always wondered about where the poetry was coming from and just had never looked into it.)

A newcomer to Penny, I have been thinking about Ruth's role in the stories and the town. After only two books, I cannot conceive of Three Pines without her but the image I've like best ( so far) is Ruth sitting on that bench in the middle of town every night at five o'clock, no matter the temperature or weather. Learning the reason for it grounded me. She's no caricature of the town grouch, she's while and complete.

I, too, am happy to know the source of the poems. Thanks for this, Courtney!